陶哲轩:数学不仅仅是严谨性和证明

原文链接:There’s more to mathematics than rigour and proofs

作者:Terry Tao

分享陶哲轩的一篇博客,与个人的一些思考不谋而合,读后受益匪浅,故转载于此。

由于 LLM 的幻觉问题,数学形式化——这一消除幻觉确保论证严谨性的手段——受到了很多关注。按照陶哲轩的说法,形式化是在前严谨阶段到严谨阶段的过渡,能避免常见错误和消除误区。然而,数学真正具有创造力和生命力的地方在于后严谨阶段。在这一阶段,研究者在已经掌握严谨理论基础的情况下,开始建立和形成数学直觉。如果 LLM 能够在后严谨阶段发挥其作用,那么它很有可能会真正引起数学学术界的广泛重视。

在开始之前,先提供一段中英对照的翻译,随后我会结合自己的理解,进行补充和探讨。

There’s more to mathematics than rigour and proofs

数学不仅仅是严谨性和证明

The history of every major galactic civilization tends to pass through three distinct and recognizable phases, those of Survival, Inquiry and Sophistication, otherwise known as the How, Why, and Where phases. For instance, the first phase is characterized by the question ‘How can we eat?’, the second by the question ‘Why do we eat?’ and the third by the question, ‘Where shall we have lunch?’ (Douglas Adams, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy“)

每个主星际文明的历史上往往会经历三个不同且可区别的阶段,即生存、探究和精致阶段,也被称为“如何”、“为什么”和“在哪里”阶段。例如,第一阶段的特点是“我们如何吃?”,第二阶段是“我们为什么吃?”,第三阶段是“我们该在哪里吃午餐?”(道格拉斯·亚当斯,《银河系漫游指南》)

One can roughly divide mathematical education into three stages:

数学教育大致可以分为三个阶段:

-

The “pre-rigorous” stage, in which mathematics is taught in an informal, intuitive manner, based on examples, fuzzy notions, and hand-waving. (For instance, calculus is usually first introduced in terms of slopes, areas, rates of change, and so forth.) The emphasis is more on computation than on theory. This stage generally lasts until the early undergraduate years.

“前严谨”阶段,以非正式、直观的方式学习数学,基于例子、模糊的概念和手势。(例如,微积分通常以斜率、面积、变化率等概念引入。)重点更多在于计算而非理论。这一阶段通常持续到本科早期。

-

The “rigorous” stage, in which one is now taught that in order to do maths “properly”, one needs to work and think in a much more precise and formal manner (e.g. re-doing calculus by using epsilons and deltas all over the place). The emphasis is now primarily on theory; and one is expected to be able to comfortably manipulate abstract mathematical objects without focusing too much on what such objects actually “mean”. This stage usually occupies the later undergraduate and early graduate years.

“严谨”阶段,此时人们被教导为了“正确”地做数学,需要以更加准确且正式的方式工作与思考(例如,通过到处使用 ε 和 δ 重新做微积分)。这一阶段重点主要在理论;人们期望能够舒适地操作抽象的数学对象,而不必过于关注这些对象实际上“意味着”什么。这一阶段通常占据本科后期和研究生早期。

-

The “post-rigorous” stage, in which one has grown comfortable with all the rigorous foundations of one’s chosen field, and is now ready to revisit and refine one’s pre-rigorous intuition on the subject, but this time with the intuition solidly buttressed by rigorous theory. (For instance, in this stage one would be able to quickly and accurately perform computations in vector calculus by using analogies with scalar calculus, or informal and semi-rigorous use of infinitesimals, big-O notation, and so forth, and be able to convert all such calculations into a rigorous argument whenever required.) The emphasis is now on applications, intuition, and the “big picture”. This stage usually occupies the late graduate years and beyond.

“后严谨”阶段,此时人们对所选领域的所有严谨基础感到自然,准备重新审视和提炼自己在该主题上的前严谨直觉,但这次直觉得到了严谨理论的坚实支撑。(例如,在这个阶段,人们能够通过与标量微积分的类比,或非正式和半严谨地使用无穷小、大 O 符号等,快速准确地进行向量微积分的计算,并能够在需要时将所有这些计算转化为严谨的论证。)这一阶段的重点在于运用、直觉和“大局观”。这一阶段通常占据研究生后期及以后。

The transition from the first stage to the second is well known to be rather traumatic, with the dreaded “proof-type questions” being the bane of many a maths undergraduate. (See also “There’s more to maths than grades and exams and methods“.) But the transition from the second to the third is equally important, and should not be forgotten.

从第一阶段到第二阶段的过渡是众所周知的,相当令人痛苦,可怕的“证明型问题”成为许多数学本科生的祸根。(另见“数学不仅仅是成绩、考试和方法”。)但从第二阶段到第三阶段的过渡同样重要,不应被忽略。

It is of course vitally important that you know how to think rigorously, as this gives you the discipline to avoid many common errors and purge many misconceptions. Unfortunately, this has the unintended consequence that “fuzzier” or “intuitive” thinking (such as heuristic reasoning, judicious extrapolation from examples, or analogies with other contexts such as physics) gets deprecated as “non-rigorous”. All too often, one ends up discarding one’s initial intuition and is only able to process mathematics at a formal level, thus getting stalled at the second stage of one’s mathematical education. (Among other things, this can impact one’s ability to read mathematical papers; an overly literal mindset can lead to “compilation errors” when one encounters even a single typo or ambiguity in such a paper.)

当然,知道如何严谨地思考是至关重要的,因为这给予了你避免常见错误和清除许多误区的纪律。不幸的是,这产生了意想不到的后果,即“更模糊”或“直觉性”的思维被贬低为“非严谨”(如启发式推理、从例子中谨慎推断或从其他学科如物理学的类比)。往往,人们最终抛弃了最初的直觉,只能在形式层面上处理数学,从而在数学教育的第二阶段停滞不前。(除此之外,这还会影响人们阅读数学论文的能力;过于字面化的思维方式会导致在遇到哪怕一个拼写错误或歧义时出现“编译错误”。)

The point of rigour is not to destroy all intuition; instead, it should be used to destroy bad intuition while clarifying and elevating good intuition. It is only with a combination of both rigorous formalism and good intuition that one can tackle complex mathematical problems; one needs the former to correctly deal with the fine details, and the latter to correctly deal with the big picture. Without one or the other, you will spend a lot of time blundering around in the dark (which can be instructive, but is highly inefficient). So once you are fully comfortable with rigorous mathematical thinking, you should revisit your intuitions on the subject and use your new thinking skills to test and refine these intuitions rather than discard them. One way to do this is to ask yourself dumb questions; another is to relearn your field.

严谨的目的不是摧毁所有直觉;相反,它应该用来摧毁坏的直觉,同时澄清和提升好的直觉。只有结合严谨的形式主义和好的直觉,才能解决复杂的数学问题;前者用于正确处理细节,后者用于正确处理大局。 没有其中之一,你将花费大量时间在黑暗中摸索(这可能具有教育意义,但效率极低)。因此,一旦你你完全适应了严谨的数学思维,你应该重新审视你在该主题上的直觉,并利用你的新思维技能测试和提炼这些直觉,而不是抛弃它们。一种方法是问自己愚蠢的问题;另一种是重新学习你的领域。

The ideal state to reach is when every heuristic argument naturally suggests its rigorous counterpart, and vice versa. Then you will be able to tackle maths problems by using both halves of your brain at once – i.e., the same way you already tackle problems in “real life”.

理想的状态是每个启发式论证自然地暗示其严谨的对应物,反之亦然。然后,你将能够通过同时使用大脑的两半来解决数学问题——即,与你日常解决“现实生活”问题的方式相同。

See also:

- Bill Thurston’s article “On proof and progress in mathematics“;

- Henri Poincare’s “Intuition and logic in mathematics“;

- this speech by Stephen Fry on the analogous phenomenon that there is more to language than grammar and spelling; and

- Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (which indicate (among other things) that there is more to morality than customs and social approval).

- Bloom’s taxonomy of learning.

相关阅读:

- 比尔·瑟斯顿的文章《关于证明和数学进展》;

- 亨利·庞加莱的《数学中的直觉与逻辑》;

- 斯蒂芬·弗莱关于语言不仅仅是语法和拼写的类似现象的演讲;以及

- 科尔伯格的道德发展阶段(其中表明(在其他方面)道德不仅仅是习俗和社会认可)。

- 布鲁姆的学习分类法。

Added later: It is perhaps worth noting that mathematicians at all three of the above stages of mathematical development can still make formal mistakes in their mathematical writing. However, the nature of these mistakes tends to be rather different, depending on what stage one is at:

后记:值得注意的是,上述三个数学发展阶段的数学家在其数学写作中仍可能犯形式错误。然而,这些错误的性质往往相当不同,取决于所处的阶段:

-

Mathematicians at the pre-rigorous stage of development often make formal errors because they are unable to understand how the rigorous mathematical formalism actually works, and are instead applying formal rules or heuristics blindly. It can often be quite difficult for such mathematicians to appreciate and correct these errors even when those errors are explicitly pointed out to them.

处于前严谨阶段的数学家常常犯形式错误,因为他们无法理解严谨的数学形式主义的实际运作方式,而是盲目地应用形式规则或启发式方法。即使这些错误被明确指出,这类数学家往往也很难理解和纠正这些错误。

-

Mathematicians at the rigorous stage of development can still make formal errors because they have not yet perfected their formal understanding, or are unable to perform enough “sanity checks” against intuition or other rules of thumb to catch, say, a sign error, or a failure to correctly verify a crucial hypothesis in a tool. However, such errors can usually be detected (and often repaired) once they are pointed out to them.

处于严谨阶段的数学家仍可能犯形式错误,因为他们尚未完善其形式理解,或无法进行足够的“合理性检查”以对抗直觉或其他经验法则,以捕捉例如符号错误,或在工具中未能正确验证关键假设。然而,一旦这些错误被指出,通常可以被发现(并且往往可以被修复)。

-

Mathematicians at the post-rigorous stage of development are not infallible, and are still capable of making formal errors in their writing. But this is often because they no longer need the formalism in order to perform high-level mathematical reasoning, and are actually proceeding largely through intuition, which is then translated (possibly incorrectly) into formal mathematical language.

处于后严谨阶段的数学家并非不会犯错,他们仍可能在写作中犯形式错误。但这往往是因为他们不再需要形式主义来进行高级数学推理,实际上主要是通过直觉进行推理,然后将直觉(可能不正确地)转化为形式数学语言。

The distinction between the three types of errors can lead to the phenomenon (which can often be quite puzzling to readers at earlier stages of mathematical development) of a mathematical argument by a post-rigorous mathematician which locally contains a number of typos and other formal errors, but is globally quite sound, with the local errors propagating for a while before being cancelled out by other local errors. (In contrast, when unchecked by a solid intuition, once an error is introduced in an argument by a pre-rigorous or rigorous mathematician, it is possible for the error to propagate out of control until one is left with complete nonsense at the end of the argument.) See this post for some further discussion of such errors, and how to read papers to compensate for them.

这三类错误之间的区别可能导致一种现象(对于处于数学发展早期阶段的读者来说,这往往相当令人困惑),即后严谨数学家的数学论证在局部包含许多拼写错误和其他形式错误,但整体上是相当合理的,局部错误传播一段时间后被其他局部错误所抵消。(相比之下,当没有坚实的直觉检查时,一旦前严谨或严谨数学家的论证中引入错误,错误可能会失控传播,直到最终得出完全荒谬的结论。)参见这篇文章,进一步讨论此类错误,以及如何阅读论文以弥补这些错误。

I discuss this topic further in this video with Brady “Numberphile” Haran.

我在与布雷迪·哈兰(Numberphile)的这个视频中进一步讨论了这个话题。

个人理解

陶哲轩在文中提到的数学教育三个阶段,与禅宗史书的经典语录有异曲同工之妙

老僧三十年前未参禅时,见山是山,见水是水。及至后来,亲见知识,有个入处,见山不是山,见水不是水。而今得个休歇处,依前见山只是山,见水只是水。

- “前严谨”阶段:通过直观和基于例子的方式接触数学,依赖直观理解和简单的推理,此阶段如同“见山是山,见水是水”。

- “严谨”阶段:开始深入学习数学的严格理论基础和抽象概念,需要改变思维方式,以更严谨的方式来思考问题,这像是“见山不是山,见水不是水”。

- “后严谨”阶段:在严谨理论基础上,再次回归直观和应用,将理论和直观结合在一起,“见山还是山,见水还是水”。

严谨阶段的过渡

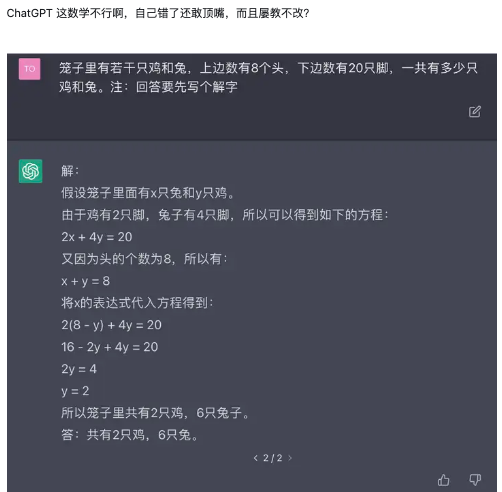

没经过严谨阶段的训练,容易犯低级的推理错误,比如 chatGPT 刚问世时,对鸡兔同笼问题的回答:

https://www.zhihu.com/question/570189639/answer/2791765600

看似正确,实则一派胡言。

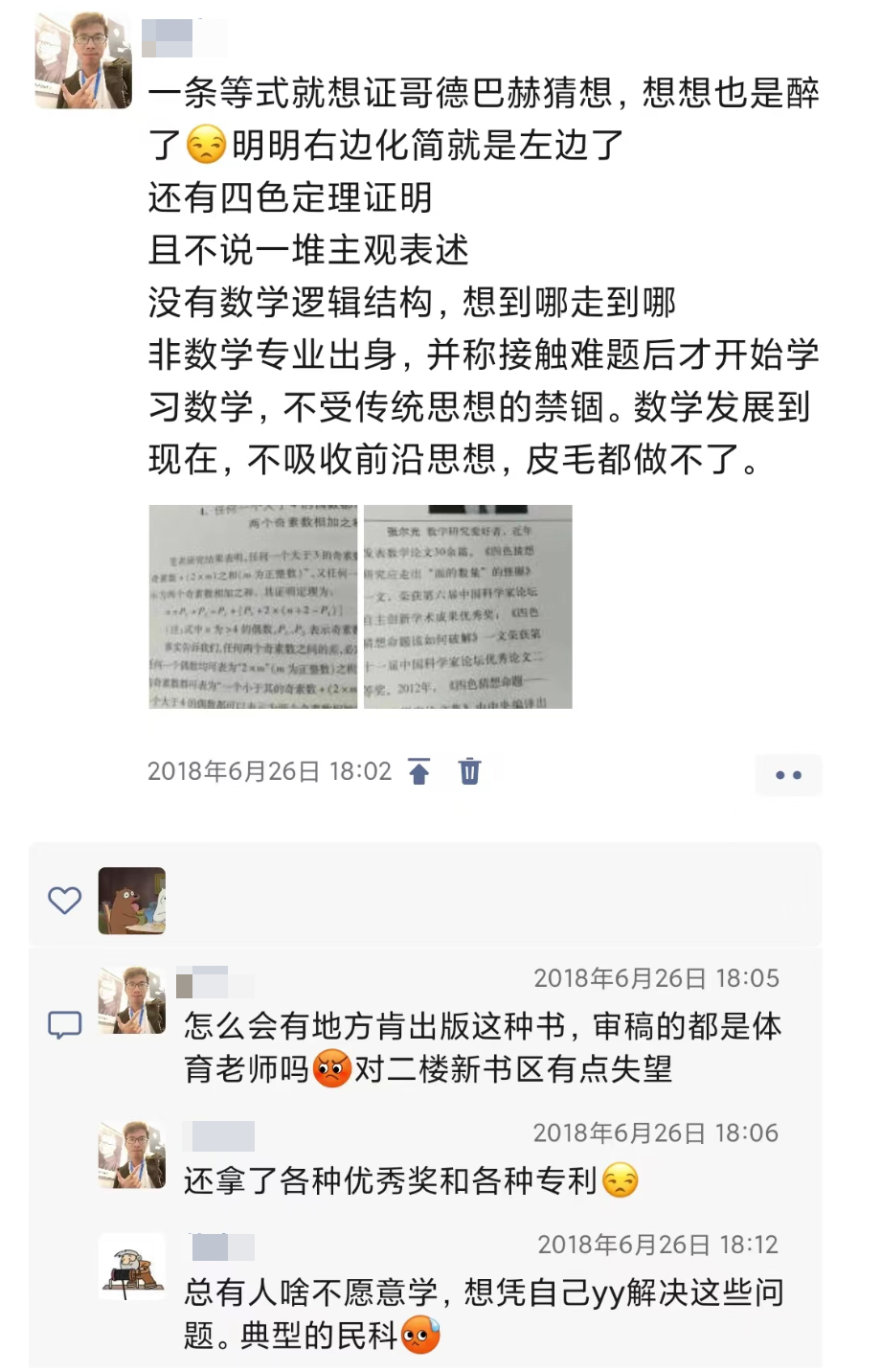

当然,不只是大模型如此,没经历严谨阶段训练的民科(“民间科学家”)也经常犯这种错误:

这也是为什么民科们宣扬的所谓“证明”经常不被主流接受或理会,因为他们往往不肯下功夫去经历严谨化的过程。

严谨阶段是必然要经历的,微积分在创立之初,没有严谨的基础,虽然在预测物理规律上取得了巨大成功,但数学逻辑上常常会导致各种谬论,引起了第二次数学危机。

相应地,就有了实数完备性理论,六条等价定理来保障微积分的严谨性。

后严谨阶段

这篇博客的重点在后严谨阶段,也即文章标题。数学不只是做题,解题,严格论证。真正重要还是贯穿其中的直觉,对理论整体的理解把握。

AI 从数学形式化,求解 IMO 竞赛题,开始过渡到对实际数学问题的把握理解。形式化可以作为后严谨阶段的语言,这个过程应该更加关注对问题的思考和直觉训练。

关于直觉的训练,DeepMind 在 2021 年的经典工作 Guided human intuition with AI 是一个很好的例子。我们在另一篇进行更深入的讨论。

很多时候,问题的价值不仅在于问题本身,更在于在思考这个问题过程中产生的直觉、形成的对问题的理解以及从中延伸出的更有价值的内容。

例如,数学中的“费马猜想”就像是“一只会下金蛋的鹅”。数学家们在对“费马猜想”(费马大定理)长达3个多世纪的研究中,发展起了很多绝妙的数学概念和理论,甚至产生了新的数学分支。(扩充了“整数”的概念;产生了“理想数”概念,开创了代数数论……)这些都是费马猜想产下的“金蛋”。

而在创造性这点,AI 的能力还没有被充分挖掘,如果 AI 很擅长形式化,那他更像一台真理机器

如果有一台真理机器只能回答是或不是,能对人类社会作多大贡献?

如果他在此基础上,能产生直觉思考,并通过严谨方式表述,那他就是一个后严谨阶段的数学家了。